Giardia lamblia

A Case Study

Lots of microorganisms can make a legitimate claim to the title of THE Poop Disease, that is, diseases that can be transmitted through human wastes. Cholera, Typhoid, Dysentery, E coli, The List Goes On And On.

In fact, some of the worst disease outbreaks in human history can be traced back to our poop.

However, to better understand disease transmission through feces, it’s good to have a simpler, and more gentle, example.

We want a disease that is both common place and less deadly; a more friendly poop disease as it were.

Might I offer, for your consideration, giadria lambia, the virus responsible for Giarda. Disease transmission works a little like this:

Disease Transmission

Grazing animals, like cows, pigs, horses, or sheep poop. This poop lands close enough to a river, lake, or stream so that it gets into the water (and the giardia lamblia virus along with it).

Downstream, humans might drink from this water. Residents might drink untreated well water. Hikers and backpackers might drink untreated water taken directly from a river or stream. The disease has now made its way into the human body. Also, so has a little bit of animal poop.

The onset of a Giardia infection typically happens within a week or so. One of the tell-tale symptoms is that it causes infected individuals to poop. A lot. Sometimes uncontrollably. For days or even weeks.

Diagnosis

It is then that an infected individual typically goes to the doctor to get a diagnosis. In order to figure out what’s wrong with the patient, the doctor needs to test….you guessed it….their poop.

Patients provide a stool sample that is then analyzed for presence of the virus. Typically, treatment involves rest and hydration for loss of fluids. This is the medical way of saying: you need to poop it out.

If that poop were to make its way into an untreated body of water, the cycle would begin anew.

For a more scientific analysis of giardia, there’s lots of great information below. Thanks for taking the time to read. Enjoy!

Life History

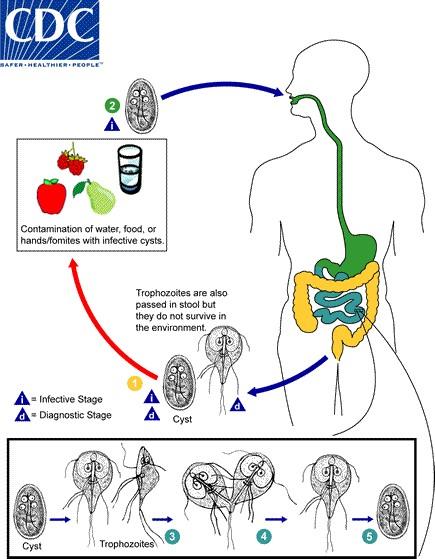

Life Cycle

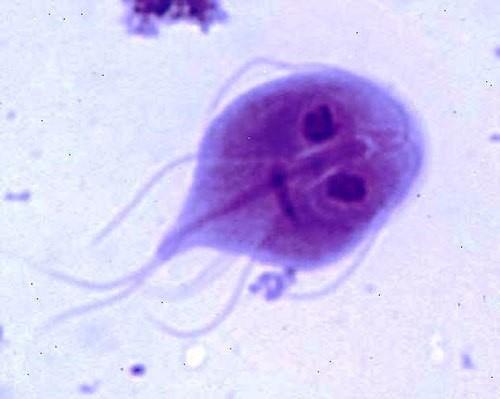

Giardia (Giardia lamblia) is an anerobic protoza. It moves by using it flagella to propel it through the water.

Giardia survives by colonizing the small intestine of several vertebrates, particularly mammals. Giardia lamblia is known to infect humans.

It was first described by von Leeuwenhoek in 1681, when he examined his own stool sample under a microscope. Giardia was not recognized as a disease pathogen until the 1970’s.

Giardia lamblia exists in two forms, an active form called a trophozoite, and an inactive form called a cyst.

The cysts have a thick cell wall that protects them from heat and cold and allows them to survive for long periods in moist environments. In untreated cold water, Giardia cysts can survive for approximately 7 weeks.

When the cyst is ingested by the host, trophozoites are released into the gastrointestinal tract where they multiply and actively feed throughout the digestive system.

The trophozoites turn into cysts as they near the colon where they are released into the environment in the host’s feces and transmitted to another host.

Microscopic Giardia lamblia is tear dropped shape and measures 9 – 21 micrometers long by 5 – 15 micrometers wide.

Giardia cysts are smooth walled and oval in shape, measuring 8 – 12 micrometers long by 7 – 10 micrometers wide.

Several Giardia species infect mammals including, dogs, cats, cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, beavers, coyotes, rodents and raccoons. Giardia is endemic to the western mountain ranges, the Rocky Mountains, Sierra Nevada, and the Cascades.

Public Health

Epidemiology

Giardiasis is very contagious. Individuals become infected after contact with contaminated foods, soil or water that has been in contact with feces carrying Giardia.

Ingestion of more than 25 cysts results in 100% infection rate, with as few as 10 cysts capable of transmitting Giardia. It’s most common in areas with poor sanitation and unsafe water.

Person to person contact is the #1 method of transmission. Water borne transmission is the second highest method of Giardiasis infection in the United State by ingestion of unfiltered water from rivers, streams, ponds and lakes.

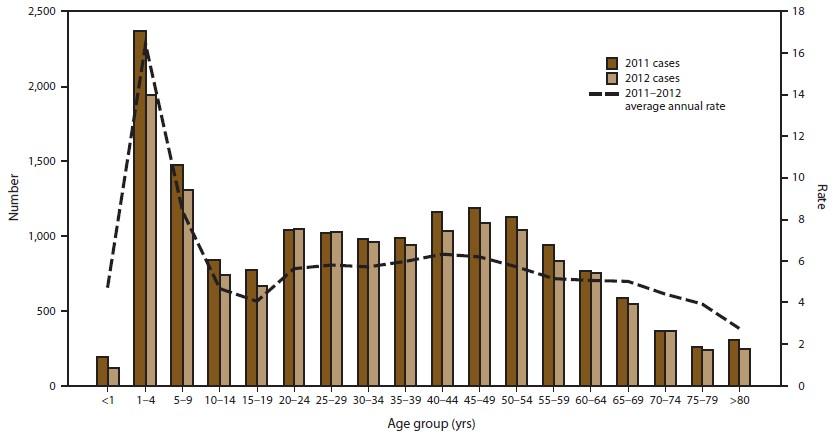

Outbreaks in the United States usually involve small water systems using untreated or inadequately treated surface water. Infection is most common July through October. Though Giardia infects people of all ages, children age 1 to 4 years old have the highest infection rate and adults 20 to 55 years old the second highest incidence of infection.

Symptoms

Symptoms usually occur one to three weeks after exposure. Symptoms include watery diarrhea, abdominal cramping, bloating, nausea, vomiting, gas, floating or unusually smelly stools, weight loss, low grade fever and loss of appetite. Symptoms may be slow in manifesting as Giardia multiply in your digestive system making gradual changes in the lining to you intestine.

Diagnosis, Treatment & Prevention

Stool samples are taken for analysis to determine if Giardia is present. Most cases of Giadisis require no special treatment. For acute cases or persistent cases an antibioitc medication can be administered.

Individuals can become infected by ingesting or coming into contact with contaminated foods, soil, or water tainted by the feces of an infected carrier. Proper hygiene, hand washing, sanitation and avoiding potentially contaminated food and untreated water are all effective means of prevention.

Wastewater Treatment & Prevention

Giardia removal in wastewater

treatment facilities and in constructed wetlands.

Giardia removal in wastewater

treatment facilities and in constructed wetlands.

Wastewater treatment plants that incorporate high rate sand filtration, ultra-filtration and UV disinfection will remove and disinfect Giardia cysts in treated effluent, Nasser el al., 2012.

High-rate sand filtration, ultrafiltration and UV disinfection were reported as the most efficient wastewater treatment methods for removal and disinfection of Giardia cysts. Treatment wetlands and ponds can also be effective.

Sources:

References

1999. Gerba, C. P., Thompson, J.A., Falabi, J.A., Watt, P.M., and M.M. Kapiscak. Optimization of artificial wetland design for removal of indicator microorganisms and pathogenic protozoa. Wat. Sci. Tech. 40, 363-368.

2004. Karim, M.R., Manshadi, F.D., Karpiscak, M.M., and C.P. Gerba. The persistence and removal of enteric pathogens in constructed wetlands. Water Res. 38: 1831-37.

2008. Reinoso, R., Torres, L.A. and E. Becares. Efficiency of natural systems for removal of bacteria and pathogenic parasites from wastewater. The Sci. Total Environ., 395(2-3):80-86.

2012. Nasser, A.M., Vaizel-Ohayon, D., Aharoni, A. and M. Revhun. Prevalence and Fate of Giardia cysts in wastewater treatment plants. J. Apply. Microbio. 113(3):477-84

Websites:

Wikipedia – The Free Encyclopedia: Giardia – Wikipedia

Center for Disease Control: Parasites – Giardia: Giardia | Parasites | CDC

Science Blog, Medical M.S. Grad Student: Life Under the Microscope: Giardia lamblia | My Kind of Science

Harvard School of Public Health: Giardiasis – Harvard Health

EPA information on Giardia: GIARDIA: DRINKING WATER FACT SHEET

Medscape: Giardiasis: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology

The Center for Food Security and Public Health; Iowa State University, college of Veterinary Medicine: Giardiasis

Constructed Wetlands in Southern Arizona: ALN No. 45: Constructed Wetlands in Southern Arizona